This piece is crafted from a talk I gave to Rosenfeld Community and is available to present in other venues. It is also an experiment to take what I had written on slides and presenter notes and use Claude.ai to craft into a written blog post. It took me several passes with corrections, additions, and iterations to get it to flow like the presentation and the way I wanted. But it was a very productive process and I feel like I got a piece which reflects my voice, my research, and seems readable.

What Lessons from the Past Can We Use to Define Futures with New Technology?

Over the past 3½ years, I worked on a book about women in interaction design, which was published in October 2025. While researching computing and design history, I learned a lot about the flow of technological innovation.

I’ve been observing the current AI boom over the past couple of years and wondering about its implications for my students, our industry, and the ongoing layoffs. As I reflect on these changes, I’m struck by the parallels to a similar transformative period in the design and printing industry during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when personal computers became dominant.

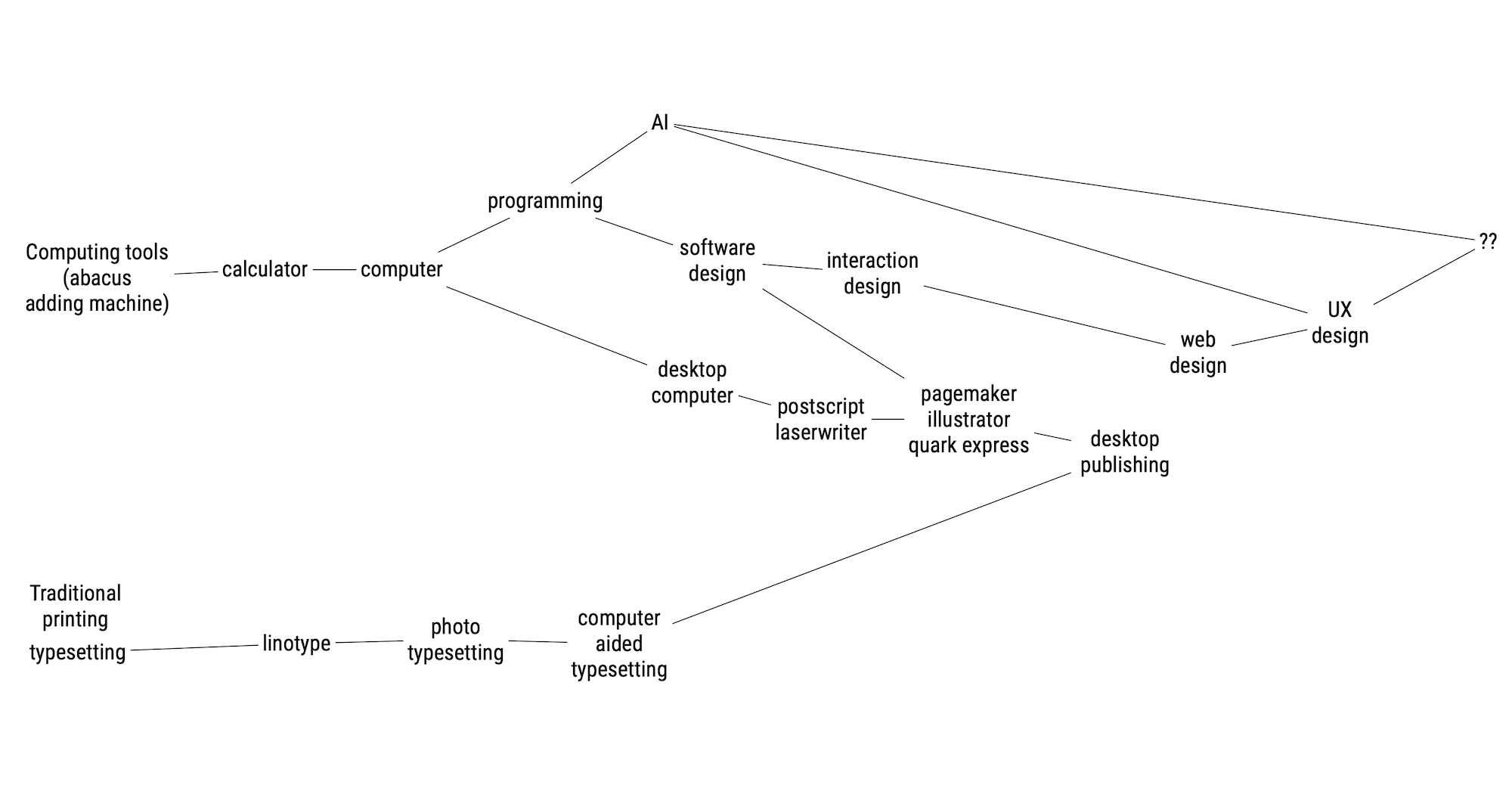

A rough flow over time (not to scale) showing parallel paths of publishing and computing. They converge at desktop publishing. Computing continues with IXD and UX design to converge with AI.

The Evolution of Typesetting

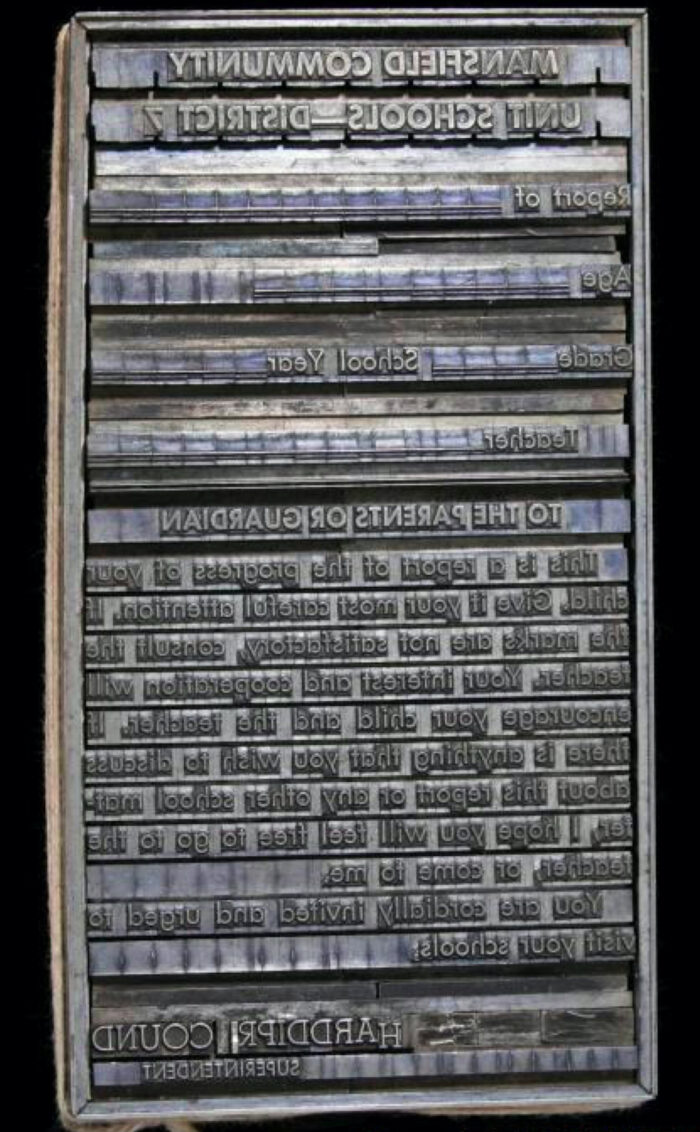

Early printing was a painstaking process. From Gutenberg until the 1920s, typesetters worked manually, setting one letter at a time using lead type. The introduction of Linotype machines in the 1920s revolutionized this process, allowing typesetters to set entire lines of type in metal, dramatically increasing production speed.

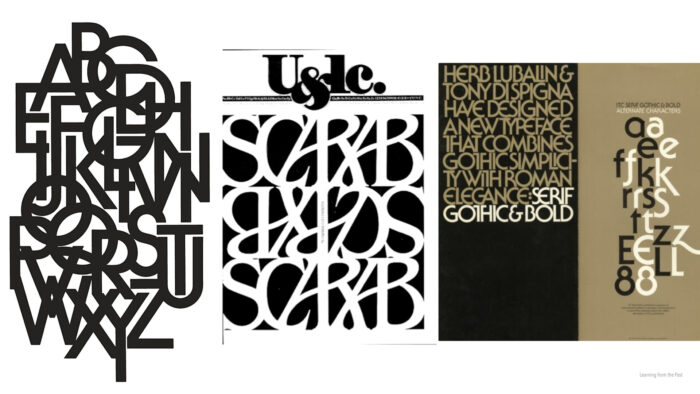

In the 1960s, phototypesetting emerged as a significant technological leap. This method replaced hot metal linotype, initially for headlines and eventually for entire text blocks. Phototypesetting allowed designers like Herb Lubalin unprecedented creativity with type. Specialized operators worked with complex machines, marking up text and creating layouts that were impossible with traditional lead type.

The transition continued with specialized typesetting machines that required deep technical knowledge. Designers were experts at understanding markup, page layout, and the intricacies of typesetting and type houses were experts with these typesetting technologies. Eventually, PostScript RIP (Raster Image Processor) would allow full-page layouts to be sent directly to pre-press, further transforming the industry.

The Computer Revolution: Key Milestones

The 1960s marked an acceleration in computer evolution, with groundbreaking developments that would reshape design and technology. In 1960, J.C.R. Licklider published “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” a prescient paper proposing more intuitive human-computer interactions. Ivan E. Sutherland’s 1962 Sketchpad—considered the grandfather of graphical user interfaces—allowed users to draw and assign constraints using a light pen and a cathode ray tube.

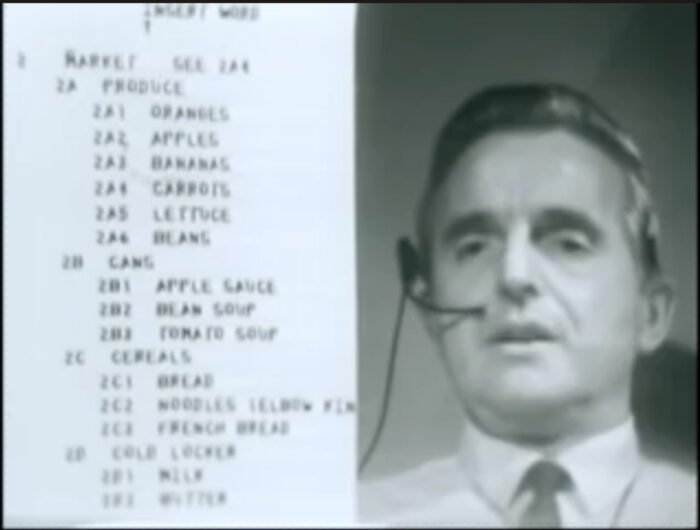

Douglas Engelbart’s work at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) represented a critical breakthrough in human-computer interaction. In December 1968, Engelbart delivered what would become known as the “Mother of All Demos,” a 90-minute presentation that fundamentally reimagined how humans might interact with computers. During this landmark demonstration, Engelbart introduced revolutionary concepts that were decades ahead of their time: a computer mouse, hypertext, video conferencing, and collaborative editing.

The demo showcased an integrated computer system where Engelbart seamlessly navigated complex tasks using a keyboard, mouse, and monitor—technologies that were nearly incomprehensible to most people at the time. He demonstrated how these tools could augment human intelligence, showing real-time text editing and information retrieval that seemed like science fiction to his contemporaries. This presentation didn’t just show new technology; it presented an entirely new paradigm of human-computer interaction.

Engelbart’s work directly influenced the researchers at Xerox PARC, who would go on to refine many of these groundbreaking concepts. The mouse, which Engelbart had developed as a tool for more intuitive computer interaction, would become a standard input device. His vision of computers as tools for human augmentation and collaborative work would become the foundation for personal computing as we know it today.

Xerox PARC: A Technological Crucible

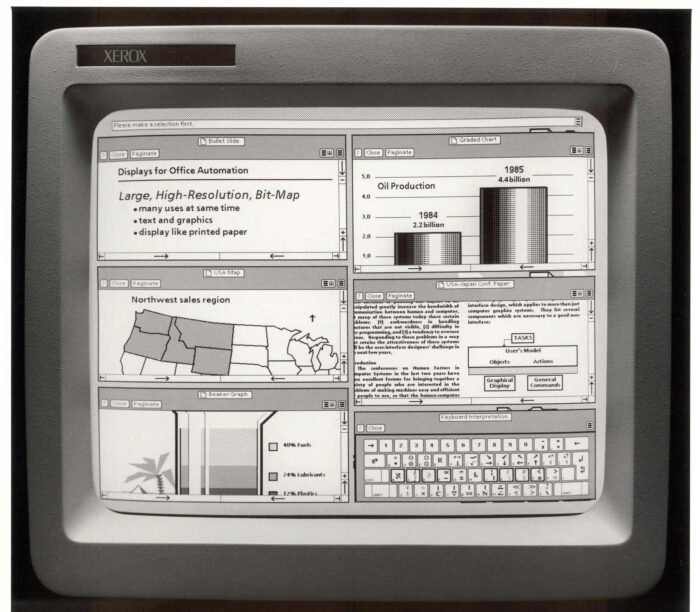

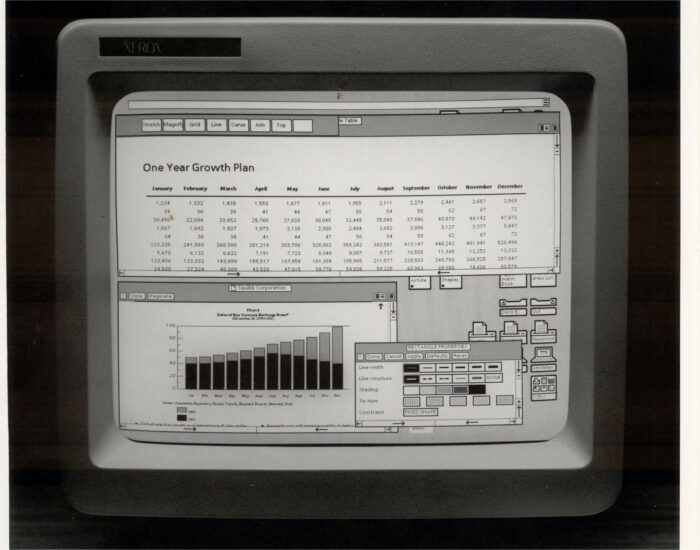

Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) was pivotal in this transformation. There were dozens of researchers, engineers and eventually designers exploring and inventing at PARC. Bill Moggridge’s firm ID Two and the designer’s there could be found at PARC exploring new innovations. Marilyn Tremaine, while working on her master’s degree, was studying cut and paste interactions by visiting offices and meticulously examining workplace editing practices. Her research would ultimately contribute to Bravo, which became Microsoft Word.

Adele Goldberg worked closely with Alan Kay, testing SmallTalk with children and documenting user interface components. Terry Roberts collaborated with Stuart Card and Alan Newell in their usability lab, testing the Star interface. Researchers like Larry Tesler developed critical interface innovations, including cut, copy, and paste keyboard commands.

Apple’s Interface Revolution

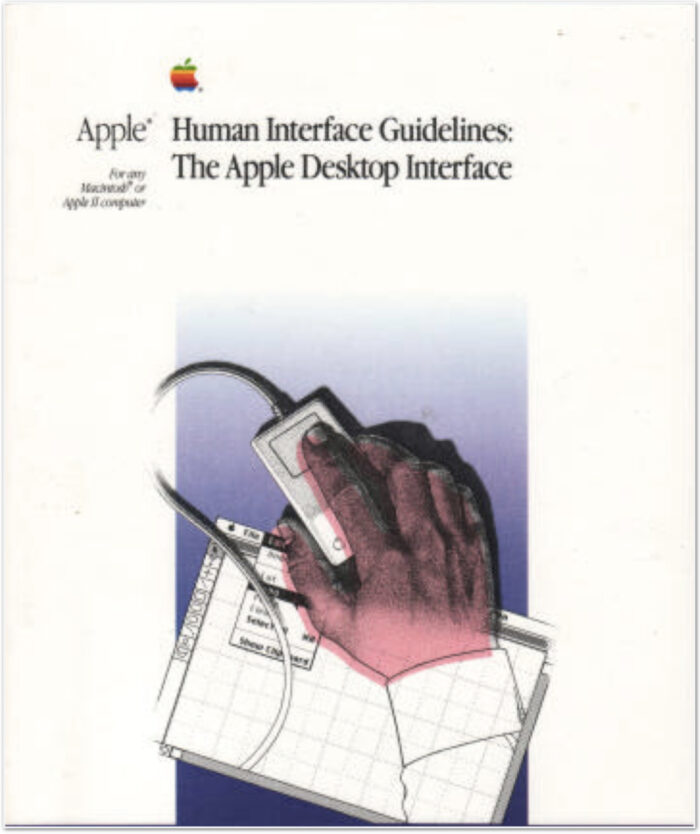

Building upon the innovations at Xerox PARC, Apple refined the graphical user interface through the pivotal work of its Human Interface Group. When Joy Mountford joined in 1986, she transformed the group into a powerful force of design innovation. The team, which expanded on Bruce Tognazzini’s initial work, developed and publicly shared the Apple Human Interface Guidelines (HIG). These guidelines were revolutionary, presenting a comprehensive set of design principles that went far beyond internal use.

By publishing these guidelines, Apple did more than create a design standard—they effectively democratized interface design. Software vendors across the industry could now learn and implement consistent, user-friendly interface principles. The HIG provided detailed case studies, taught user testing methodologies, and created a shared language for interface design. The team presented at CHI conferences and openly shared their research, ensuring that the ecosystem of Macintosh software became increasingly intuitive and accessible.

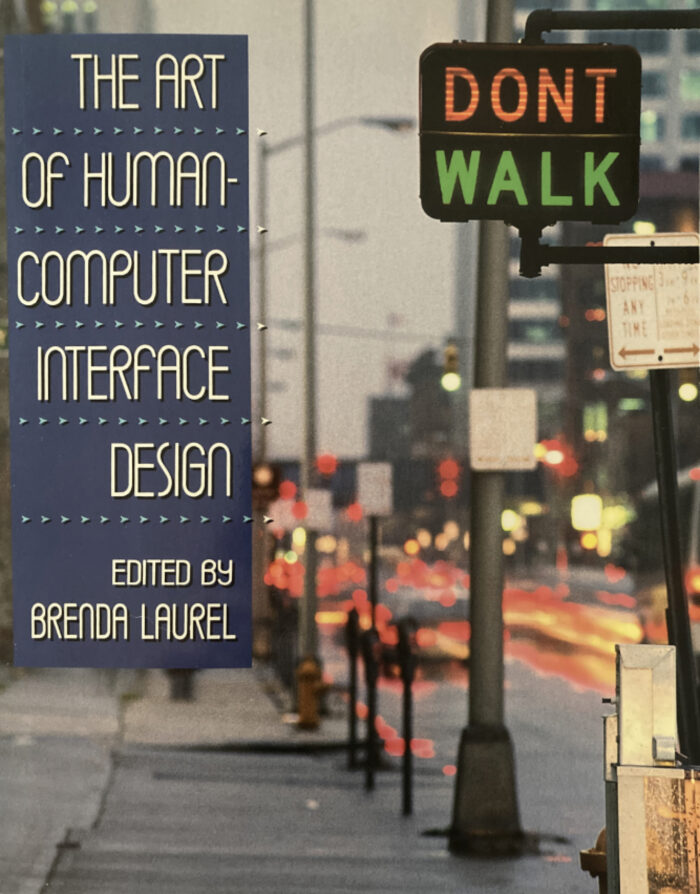

The book The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, conceived by Joy Mountford and edited by Brenda Laurel, became a seminal text. Written by members of the HIG and Advanced Technology Group, it further spread the principles of thoughtful, user-centered design. This approach was critical in enabling the desktop publishing wave, making complex technology approachable for a broader range of professionals.

The Desktop Publishing Revolution

The emergence of PostScript and desktop publishing software fundamentally transformed the design world. Chuck Geschke and John Warnock at PARC developed a device-independent graphics system that would become PostScript. Released in 1984, PostScript worked in conjunction with Apple’s LaserWriter to create the first true WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) publishing environment.

In 1985, Paul Brainerd of Aldus Corporation coined the term “desktop publishing” and launched PageMaker, a groundbreaking software that, combined with Adobe’s PostScript and Apple’s LaserWriter, created the desktop publishing revolution. PageMaker allowed professionals to design pages on a computer that could be printed exactly as they appeared on screen, a radical concept at the time.

Adobe continued to innovate with Illustrator in 1987 and Photoshop in 1990 (developed by John and Thomas Knoll). Quark XPress, which started in 1981 and arrived for the Macintosh in 1987, would become another prominent desktop publishing tool, overtaking PageMaker during the 1990s. Linotype was the first graphic arts supplier to recognize PostScript’s value, quickly followed by other manufacturers.

The Human Cost of Technological Transformation

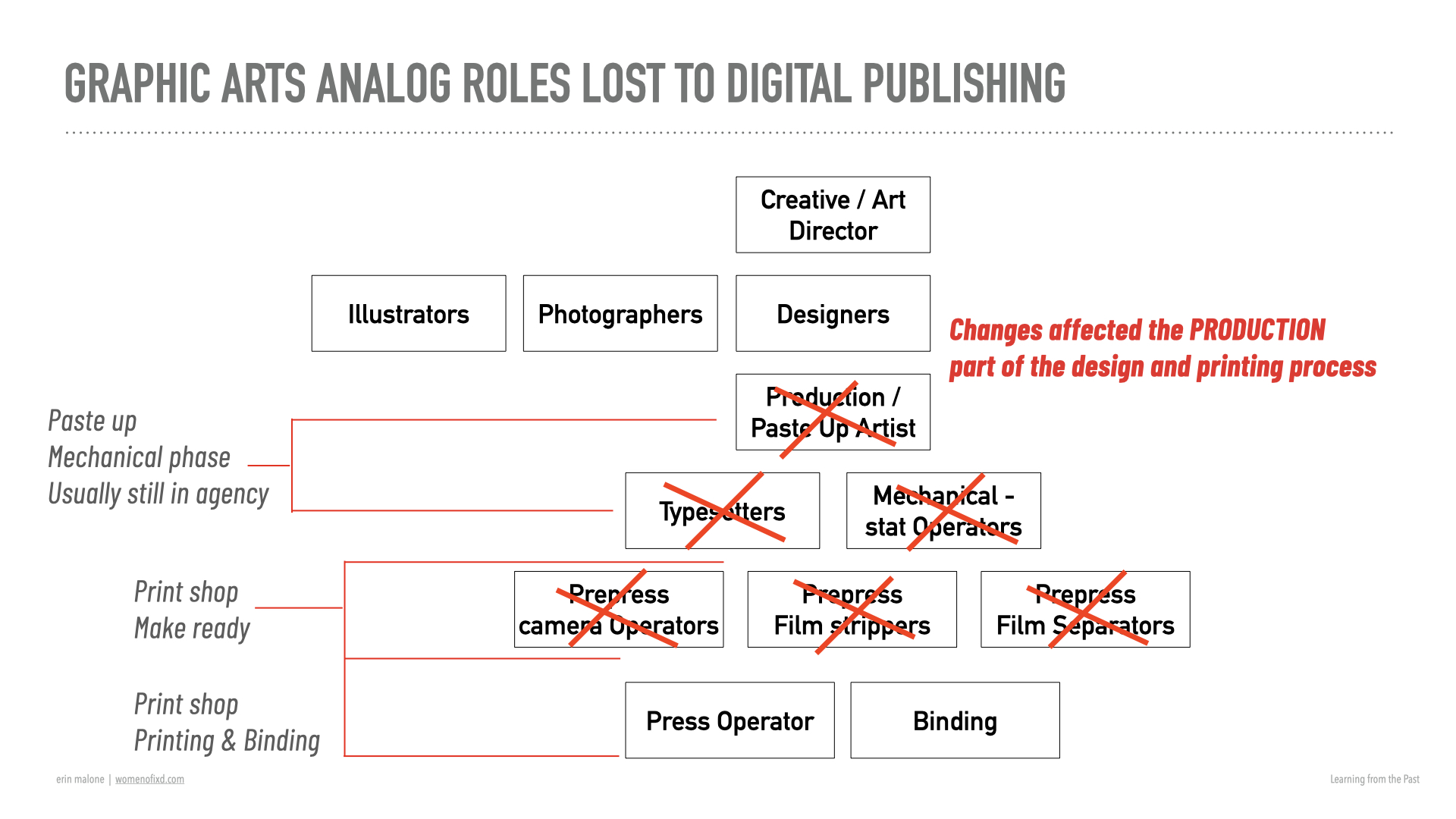

The desktop publishing revolution didn’t just change technology—it fundamentally reshaped the workforce. Entire categories of production roles disappeared almost overnight. Paste-up artists, who meticulously arranged physical layouts with precision and skill, found their craft obsolete. Typesetters who had spent years mastering complex machines became redundant. Mechanical stat operators, pre-press camera operators, film separators, and film strippers—professionals who had been critical to the print production process—suddenly found themselves without a place in the new digital workflow.

These roles, which had required considerable expertise and had been central to graphic production for decades, were eliminated by software that could perform their tasks more quickly and consistently. The transition was brutal and swift, with many skilled professionals forced to retrain or leave the industry entirely. It was a stark reminder that technological progress, while innovative, often comes at a significant human cost.

AI: The New Technological Disruption

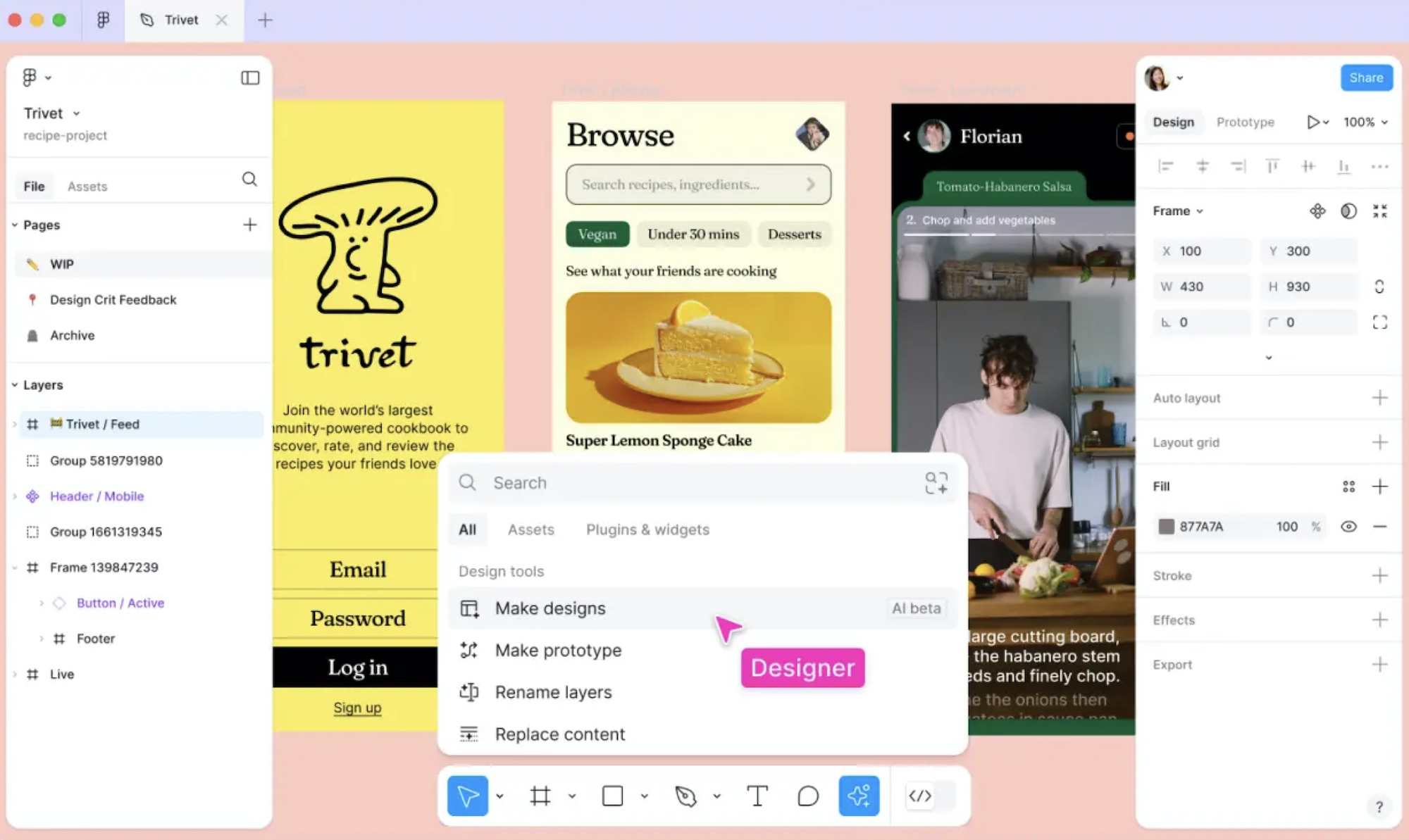

Just as desktop publishing revolutionized design, AI is poised to reshape multiple industries. Tools like Figma, Adobe’s AI features, and Canva are already automating tasks traditionally performed by designers and content creators.

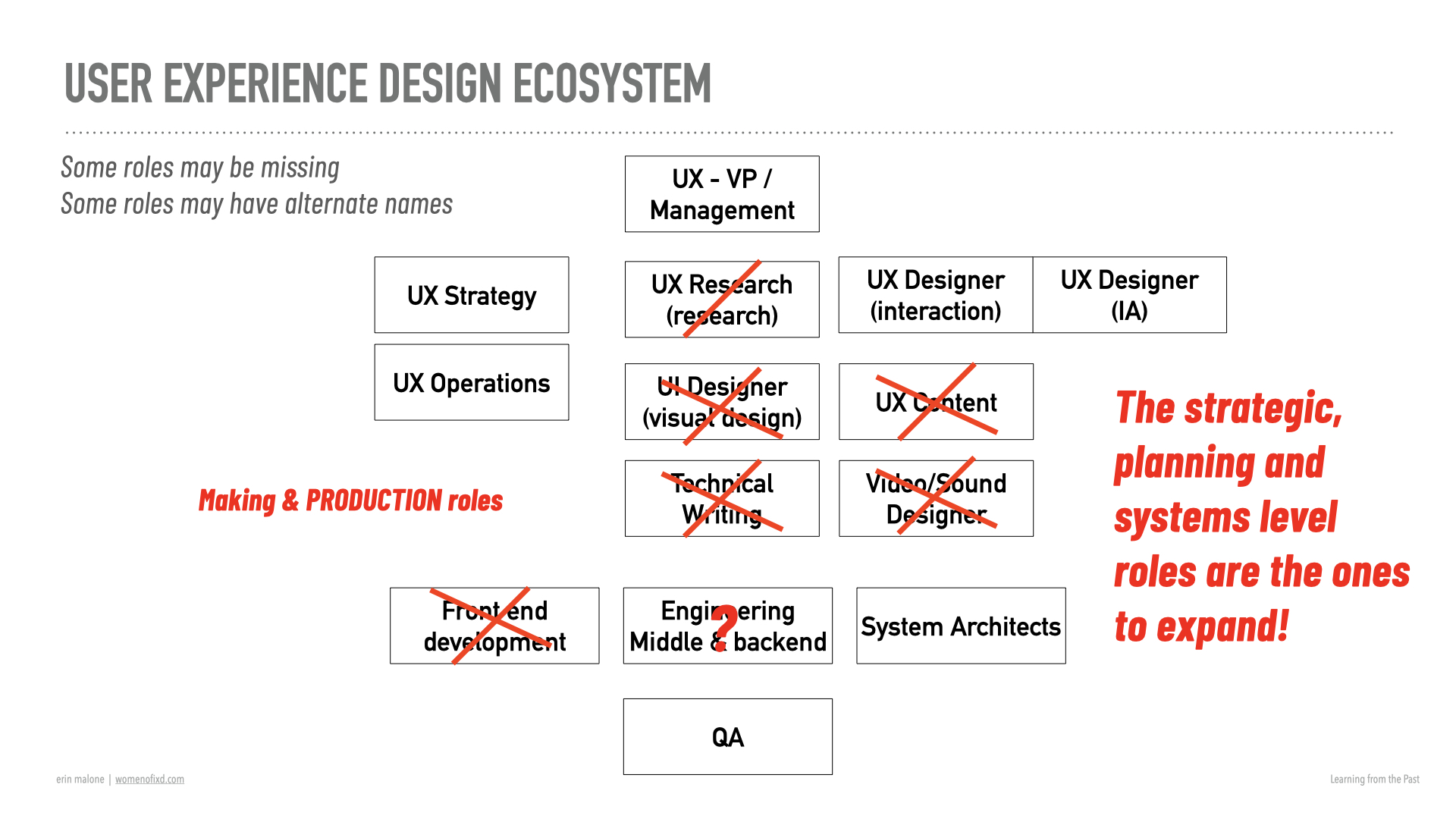

The current design ecosystem faces significant disruption across multiple roles. UI designers may find their layout and design generation tasks increasingly automated, with AI tools capable of creating entire interface mockups from simple prompts. UX content writers and technical writers are at risk as AI demonstrates growing capabilities in generating clear, structured documentation and microcopy. Video and sound designers face competition from AI tools that can generate and edit multimedia content with increasing sophistication.

Front-end developers are particularly vulnerable, with AI coding assistants now capable of generating entire code snippets, components, and even complete page layouts. Parts of UX research are being challenged by AI’s ability to synthesize user feedback, generate personas, and provide initial insights. Even middle and back-end engineering roles are not immune, with AI showing potential to automate code generation, debugging, and system architecture tasks.

Production roles are most at risk, while strategic and systems-level positions are likely to expand. As Scott Berkun aptly notes, the challenge is shifting from “making” to “deciding what to make.”

Navigating the AI Landscape

My advice to students and professionals mirrors insights from thought leaders like Jorge Arango and Christina Wodtke: embrace experimentation and continuous learning. As Wodtke says, “AI Won’t Take Your Job—But Someone Who Uses It Better Than You Will.”

The evolution from traditional production to desktop publishing took 30-35 years.

AI’s transformation feels accelerated, but the groundwork has been quietly laid through years of software integration. The key is to repackage existing skills, rebrand professional identities, partner with those defining the new technological landscape, and continue to be curious and learn new ways of working.

We must craft compelling narratives that position ourselves strategically in this emerging world. Some skills are already within us — we just need to adapt and evolve — using what we do well, layered with new skills which take advantage of AI to expand our capabilities rather than replace us.

Resources to get your head around this space:

Lou Rosenfeld: AI is the future of UX. Here’s how to prepare.

Jorge Arango: Envisioning (Near-)Future IA Design

Christina Wodtke: AI Won’t Take Your Job-But Someone Who Uses it Better than You Will

Scott Berkun: Will AI really eleminate design jobs?

Resources to learn more about AI Ethics and biases in AI

Women in AI Ethics: https://womeninaiethics.org/

Algorithmic Justice League: https://www.ajl.org/

Ethics of AI from UNESCO: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics

AI Now Institute: https://ainowinstitute.org/

Algorithm Watch: https://algorithmwatch.org/en/

UC Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible AI: https://humancompatible.ai/